- History of Endometriosis in the late 17th and 18th centuries

- A controversial history

- The role of chocolate cysts in the discovery of endometriosis

- The understanding of endometriosis in the late 19th and 20th centuries

- Advances in the understanding and treatment of endometriosis

- History of endometriosis and Modern advances

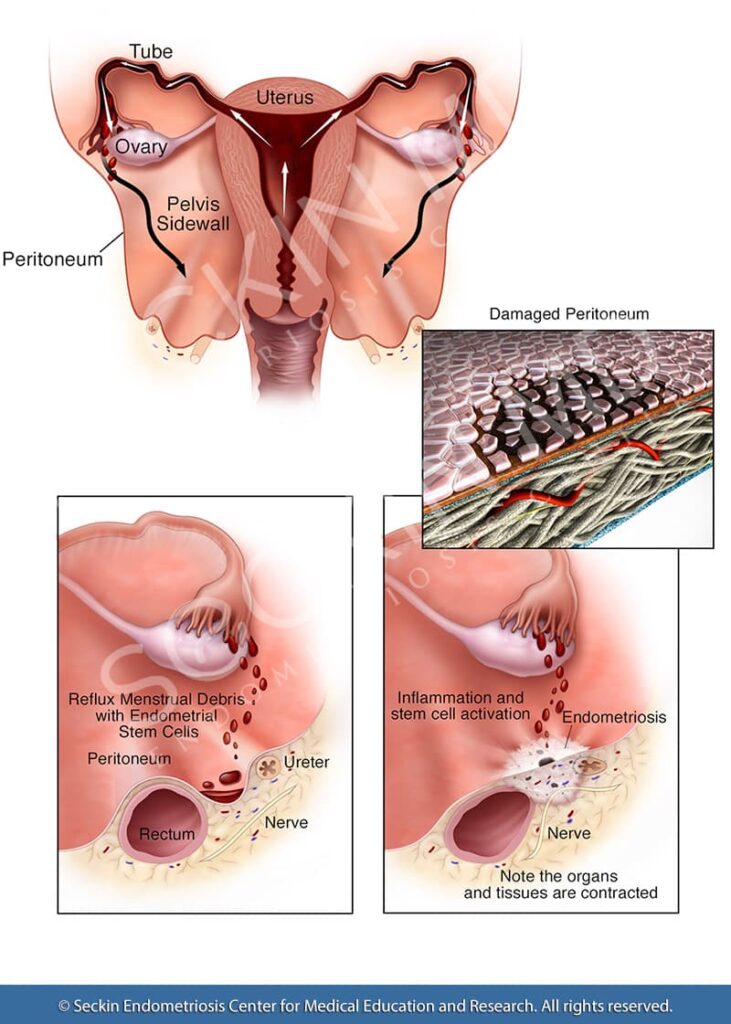

Endometriosis is a debilitating chronic disease that can affect women of reproductive age and beyond. It occurs when tissue resembling the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) grows in other parts of the body. Endometriosis can cause symptoms such as painful and heavy periods, chronic pelvic pain, fatigue, and infertility. While there have been many advances in endometriosis research in recent years, the disease itself is not a new discovery. In fact, it was first identified nearly 300 years ago with ancient origins traced to more than 4,000 years ago. Here is a brief history of endometriosis.

History of Endometriosis in the late 17th and 18th centuries

In 1690, German physician Daniel Shroen wrote about “peritoneal ulcers that tended to form lesions”. He described lesions that expanded in size and were susceptible to hemorrhage. Shroen had stated that these lesions were “female disorders characteristic of those who are sexually maturing”.

After Shroen’s study, 11 other studies from other parts of Europe have documented similar findings. Though they lacked the sophisticated histological methods available today, these studies greatly detailed the pathology of the disease. They also noted that it could lead to miscarriages and sterility.

Chronic pelvic pain is one of the characteristic symptoms of endometriosis. In 1776, Scottish physician Louis Brotherson talked about the pain experienced by women during the worst stages of this disease. He also said that it affected them adversely. They lived in fear of their symptoms.

The 18th century saw the rise of postmortem examination of endometrial lesions. Scottish physician William Broughton and English physician Robert Tailford described proliferating structures that later came to be identified as being polyp-like. Other physicians also observed a pattern of spreading inflammation around the vagina. Eventually, by the 19th century, physicians were able to identify features such as chocolate cysts in the ovaries.

A controversial history

Knapp’s findings were not without controversy. Doctors Giuseppe Benagiano and Ivo Brosens questioned Knapp’s rationale for attributing the first study of endometriosis to Daniel Shroen. They reasoned that his findings overlooked the definitive pathology of the disease such as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity and the benign nature of these lesions. The other aspect that raises questions on 18th – century depictions of what was apparently endometriosis is that there was no abdominal surgery technique that could comprehensively confirm these were indeed endometriotic lesions.

Instead, Benagiano and colleagues think that in 1860, Carl Rokitansky had the first intuition that endometrial glands and stroma could be present in the ovaries. However, the authors noted that this is not a proper ovarian endometrioma. Rokitansky himself described them as sarcomas, which is known not to be the case, and apparently, had his own personal definition for the term. Nevertheless, Rokitansky identified three appearances (phenotypes) of what could likely be the first pathological description of endometriosis. He described features such as the invasion of the muscular uterine wall, the formation of a polyp, and the invasion of the ovaries.

The role of chocolate cysts in the discovery of endometriosis

Endometrioma is endometriosis in the ovaries. It is characterized by cysts made of menstrual debris and inflammatory enzymes. Given their appearance, these cysts are called “chocolate cysts”.

The description of chocolate cysts plays a central role in the discovery of endometriosis. This was first illustrated by Russel WW in 1899. Russel described a case of a pre-menopausal woman who underwent surgery for cystic adenocarcinoma of the left ovary. Russel noted microscopical areas that were a “prototype of the uterine glands and interglandular connective tissue”. Many such findings followed suit in the coming years with Dr. John A. Sampson detailing 37 cases of chocolate cysts by 1922.

The understanding of endometriosis in the late 19th and 20th centuries

The discovery of chocolate cysts also paved the way for the postulation of several theories explaining peritoneal endometriosis. While Sampson proposed the rupture of the cyst as the main cause, others postulated that endometrial lesions could have arrived inside the ovary via the lymphatic system. Alternatively, the outer lesions could have invaded the ovary, they said. Sampson’s 1927 article titled, “Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity” is the first to officially use the term “endometriosis”.

While the scientific understanding of endometriosis was still shaping up, prevailing customs and societal beliefs of the era continued to influence a large part of disease treatment. Techniques back in the late 19th century included non-surgical interventions, electrocautery, dilation and curettage, partial excisions, oophorectomy, and hysterectomy, among others. So far, there has been no evidence that doctors used endoscopic techniques during this period.

Cullen’s description

Before Sampson first used the term endometriosis and ascribed the possible origins of the disease to retrograde menstruation, the Canadian surgeon Dr. Thomas Cullen was the first to present both a morphological and a clinical understanding of adenomyosis and endometriosis in 1882. Many of his pathology peers rejected his views. But Cullen had collected 90 uteri with adenomyosis (endometriosis of the uterine wall) and described all their features. His findings revealed that these growths of adenomyosis were endometrial in origin. By 1920, Cullen provided a list of possible sites for adenomyotic lesions in the pelvis.

The 20th century saw several advances in disease understanding aided by new techniques like laparoscopy. This was also the period where endometriosis started becoming distinguishable from adenomyosis. Cullen’s microscopic observations confirmed that glands surrounded by normal mucosal stroma were a defining feature of endometriosis.

Cullen’s pioneering discoveries included the first description of kidney damage due to endometriosis and the recognition that hysterectomy does not necessarily cure the disease. We, at Seckin Endometriosis Center, are also of the firm belief that a hysterectomy should only be a last resort.

Endometriosis in other areas

The 1930s and 1940s saw descriptions history of endometriosis in the lungs, bowels, colon, rectum, bladder, lymph nodes, cervix, and other places.

The discovery of endometriosis in teenagers by Dr. J. Fallon in 1946 prompted research on the condition in this population. This was also the time when animal models of endometriosis were being studied. By the end of the 1940s, clinical trials and surveys were in vogue.

However, societal perceptions of endometriosis were still akin to the previous eras. Physicians continued to urge women to have children sooner as by now the potential impact of endometriosis on fertility had become clear. In fact, for the most part of the 20th century, endometriosis was misdiagnosed as sexually transmitted pelvic inflammatory disease! To make matters worse, pelvic pain was still being linked to mental illness and promiscuity as well.

Advances in the understanding and treatment of endometriosis

The period between 1950 and to late 1970 saw great advances in surgical techniques. Surgeons were still relying on open abdominal surgeries (laparotomies) and hysterectomies. However, microsurgical methods such as laparoscopy started gaining prominence, particularly for diagnosis with notable contributions by Dr. Raoul Palmer in 1955 and Dr. Hans Fragenheim in 1958 in the field of color live laparoscopy. However, only a handful of surgeons were successful with early, pre-video laparoscopy, which meant that many surgeries continued to do laparotomies and hysterectomies.

First laparoscopic hysterectomy

The late 1970s saw great advances in the understanding and treatment of endometriosis. The first demonstration of laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed by Dr. Harry Reich in 1989. Dr. Reich showed that it is. This was the cornerstone history of endometriosis.

possible to perform a hysterectomy with laparoscopy followed by vaginal uterine removal. With the experience of more than 5,000 laparoscopic surgeries, Dr. Reich has long advocated the need for a hands-on approach to laparoscopic excision surgery. The surgeon can properly see and feel the endometriotic lesions only in this way according to Dr. Reich. Subsequently, Drs. Camran, Ceana, and Farr Nezhat proved the effectiveness of laparoscopic treatment in several complicated cases of endometriosis.

By now, it was becoming increasingly evident that minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopy allowed for lower mortality. It also improved access and visualization of difficult-to-reach areas, increased precision, decreased blood loss and pain, and led to faster recovery. Many surgeons soon started adopting this route.

The main limiting factors in performing a successful laparoscopic excision surgery are the skill of the surgeon and access to proper instrumentation. At Seckin Endometriosis Center, Dr. Seckin and his team are experts in laparoscopic techniques and have the necessary skill and technical know-how to treat even the most complex cases with minimal discomfort and with the aim of preserving fertility.

History of endometriosis and Modern advances

Advances in endometriosis knowledge and treatment continued well into the 80s and 90s. Techniques such as single-port laparoscopy introduced by Dr. M.A. Pelosi and Dr. Robert L. Barbieri’s study on the role of the CA-125 glycoprotein as a potential biomarker for endometriosis were some of the other pioneering advancements.

The research was also underway on deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, prostaglandin inhibitors, and the role of immune dysfunction in endometriosis. In 2004, Dr. Linda C. Giudice contributed much to the genetic and molecular understanding of endometriosis. This was followed by Dr. Hugh S. Taylor and colleagues’ discovery of a mutation in the KRAS gene in 2012 and its association with endometriosis.

New discoveries about the development of endometriosis include the role of stem cells in menstrual blood as a complementary explanation for retrograde menstruation and advances in the treatment of endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers.

The rapid growth of new knowledge in the understanding of the etiology and treatment of endometriosis also brought with it the need to remove many misconceptions about the disease and provide easily accessible resources for patients and caregivers. Many non-profit organizations and support groups brought clinicians, researchers, and patients onto a common platform. Prominent among them include the Endometriosis Association by Mary Lou Ballweg and Carolyn Keith in 1980, Endometriosis.org by Lone Hummelshoj in 2005, and the Endometriosis Foundation of America by Dr. Tamer Seckin and Padma Lakshmi in 2009. This is Dr. Tamer Seckin’s contribution to the history of endometriosis.

Get a Second Opinion

Our endometriosis specialists are dedicated to providing patients with expert care. Whether you have been diagnosed or are looking to find a doctor, they are ready to help.Our office is located on 872 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10065.

You may call us at (646) 960-3080 or have your case reviewed by clicking here.

Dr. Seckin is an endometriosis specialist and women’s reproductive health advocate. He has been in private practice for over 30 years at Lenox Hill Hospital with a team of highly skilled personnel.

Dr. Seckin specializes in advanced laparoscopic procedures and is recognized for his expertise in complex cases of deep infiltrating endometriosis of the pelvis. He is particularly dedicated to performing fertility-preserving surgeries on cases involving the ovaries.

He has developed patented surgical techniques, most notably the “Aqua Blue Excision” technique for a better visualization of endometriosis lesions. His surgical techniques are based on precision and microsurgery, emphasizing organ and fertility preservation, and adhesion and pain prevention.

Dr. Seckin is considered a pioneer and advocate in the field of endometriosis.